TOBIAS GRAU BUILDING

OFFICES/WAREHOUSE/FACTORY

RELLINGEN

GROSS FLOOR AREA 4,160 SQ M

BUILT APRIL 1997–APRIL 1998, JULY 2000–JULY 2001

BDA SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN ARCHITEKTURPREIS 1999

It is not the construction but the automotive industry that appears to have a monopoly on the term “formal expression.” Independent of functional considerations and technical particularities

that are understood by only a few, “formal expression,” as it appears in the media, is presented as an important argument to buy, constituting a discrete qualitative feature. Only if a car’s form “speaks” does

it define brand image; and only then does it say: “The front and back of the car, through their design, express youthful appeal and charm” (Mercedes). A BMW, on the other hand, is sold as a piece of

“high tech, high emotion” sporting equipment. In architecture, the quality of form is neither conveyed nor discussed. There is no sensibility for it, in contrast to the automobile. And yet, even in the field

of architecture, emotion and image are defined via form—which becomes evident once advertisers seek an architectural framework on an equal footing with the car in order to stress mobile elegance

and formal expression. Or, the other way round (as in the case of Audi), once they realize they have been stuck with banal architecture.

Despite all the euphoria for the terms “UFO” and “spaceship” in current architectural debate, Tobias Grau’s silver space station, located in the industrial area of Rellingen and now appearing in

duplicate, remains the only real example of spaceship-like design in Germany (at least according to the client). It draws inspiration from the concept of art as design science developed by Buckminster

Fuller and Jean Prouvé. In historical terms, Fuller’s Dymaxion Dwelling Machine is arguably architecture’s most significant attempt to solve the problem of industrial design. By simple structural

means—and via the World Wide Web—the Tobias Grau spaceship on the periphery of Hamburg, as a major industrial building, launches the inner emotionality of the “house” into the outer orbit

of a “spatial object.” At the same time, it is a striking representation of the company

The Natwest Media Center on Lord’s Cricket Grounds has become something of a cult object. Designed in 1999 by the English architecture group Future Systems, it is the first double-shelled building to

be made entirely of aluminum. Like the ribs and rafters used in plane and ship construction, the 100-ton semi-monocoque structure is formed by rows of welded-together I-section ribs and sheet metal strips with a maximum size of 4.5 meters by 20 meters. The giant pod, which was in fact

constructed in a boatyard, has an outer metal skin ranging in thickness from 6 to 20 millimeters. The resulting shape, with its double curves, is far more dramatic than a simple cube. In addition, the shell structure eliminates the need for exterior cladding and interior pillars. The oversize

“viewfinder,” which stands on two 15-meter-high cement towers, does not even make use of an expansion joint; on the outside, it has merely been painted like the hull of a ship. It has only one shortcoming: the price.

Costs rose from 2.3 million to 5.8 million pounds, in part because no airconditioning system was initially planned. The panoramic windows (behind which 120 journalists sit in four rows) have a 25-degree tilt, and they can only be opened slightly, making it difficult to ventilate the space.

“The very least one could expect of sculpture is that it moves,” Salvador Dalí once said while standing in front of one of Alexander Calder’s first “Mobiles.” In the mid-1960s, the revolutionaries from Archigram

sought to escape this dictate with architectural mobiles that one could fly away on like airships: “We couldn’t resist the idea of ‘Instant City’ hovering in from nowhere, landing and then gathering up its skirt and disappearing at the end of events.” In 1992, Claude Vasconi conducted the last mobile experiment of this kind before a crowd of 1,200 people on a stage in Weimar that resembled a medieval traveling theater. His half organic, half galactic aluminum capsule, which stood on telescopic legs and was accessible via airport gangways, resembled a spider about to skitter away. The 1999 project in the capital of culture was never realized due to estimated construction costs of 12.5 million euro—which were to be raised by private investors.

The aerodynamic space station, which appears to have taken a second-row seat only by accident (and only temporarily), also toys with such themes as technology, machinery, dynamics, and mobility. The spaceship image is consistent right down to the contrasting archaic gangway that, in line with flight control regulations, appears to have been moved up to the cabin door by ground personnel. Even so, the silver idea accelerator, with a dark-blue solar drive in the glass tailpiece, remains motionless. A disappointment? After all, seventy years ago, Angelo Invernizzi pulled off the engineering feat of a revolving house, which he constructed in shiny aluminum: the Casa Girasole in Marcellise near ظerona. This building demonstrates the surprisingly long history of architectural “inventions.” The rotating eco-house by the Freiburg architect Rolf Disch, however, is nothing more than an oversized gimmick.

Naturally, the crosssection of BRT’s hovercraft is not an innovation in the sense of patent law. “Innovation,” writes the art historian Boris Groys, “does not involve uncovering an element previously concealed, but rather reassessing something that we are familiar with.” The history of transforming vertical glass cylinders into large horizontal forms goes back to “Mega Bridge,” developed by Raimund Abraham in 1965. As early as 1931, though, Jakov Cernichov adopted this motif for his chemical

plant. In 1972, Coop Himmelblau unveiled the project “Frischzelle” (Live Cell), a vertical, bioclimatic park/recreational facility in the form of a rooftop glass survival tank. In 1968, there were plans to expand the historical building of the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie (Academy of Art) using two translucent cylinders 15 meters in diameter and 120 meters long.

Twenty years later, Toyo Ito designed an end structure for the Yatsushiro Historical Museum that was related typographically and had a freely designed cross section. In 1990, one year prior to the founding of BRT, William Alsop used the dynamic motif several times: for the British EXPO pavilion in Seville, the Hamburg ferry terminal, the local government headquarters in Marseille, and the Cardiff Bay visitor center. Only the last two designs were realized in their original form. The single-level steel structure in Cardiff, which has an elliptic crosssection and stands above the ground, features abstract-decorative, organically shaped lighting openings in the outer skin, which is made of plywood and a weatherproof

fabric covering. These counteract its high-tech image. So much for the typological background.

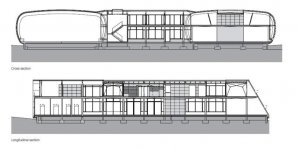

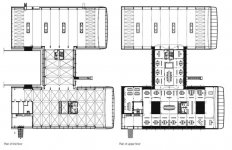

The building designed by BRT is based on similar concepts, also viewing the building as passageway, location as path, roof as main floor, and single shape as a quantum leap to new dimensions. However,

there are many differences, including its emphasis on economy and ecology. As a lamp designer’s headquarters, the two-story spacecraft unites very diverse functional areas: the upper floor accommodates a lobby, the development department (with a showroom for dealers), and the cafeteria. The ground floor houses the shipping department, a final assembly unit and a warehouse. More offices are located in the linking section, and there is additional warehouse space in the second tube. The first tube, 58 meters long and 24 meters wide, is divided into three sections and contains two atriums not visible from the outside. When it was expanded, its typology necessitated opening the structure on its longitudinal sides. This was done without adversely affecting the persuasive power of its formal design or interfering with the “flight safety” of a body that appears to be hovering just above the ground. In spite of the visible camber of the “floor panel,” the cross section remains a stabile architectural motif, thanks to its southern facade and the fascinating aesthetics of subdivided space. The ship is “stabile,” as Hans Arp would say, not “mobile” in Marcel Duchamp’s sense.

The architects did not intend to parody or fetishize 1970s Pop Art, whose naive enthusiasm for technology and the moon landing were always shaky. Even the machine aesthetic of the 1983 dental lab by Shin Takamatsu—imitating a locomotive—would be an anachronism. After all, who would want to interpret this building as a lamp in postmodernist fashion? Such an association—though effective for corporate identity— could only be triggered by the concept of the single form as implemented in the lobby lighting. No, the well-rehearsed spatial magicians from BRT were seeking a consistent, independent, functional and, above all, moving design for an industrial building that is part factory, think tank, and showroom. The flying object in Rellingen has broken free of the sphere of imagination. Rub your eyes all you want—Le Corbusier’s vision from 1922 has become reality: “If a structure is to be given the full glory of its form in the light of day, with its outer skin adapted to user-related requirements, the elements that suggest and create form must assert themselves in the structuring of the outer skin.” Nowhere is this demand more clearly fulfilled than here. Generally, the successful self-definition and self-portrayal of a firm via architecture must be in proportion to cost (though Foster’s

Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank and the examples mentioned at the beginning are exceptions). However, the cost—which is primarily planning- related—will be seen in a new light if the client realizes what slips

through his fingers with a building that does not make a strong architectural statement. The Tobias Grau building, which was the subject of a private competition, is proof of this. Construction costs were roughly the same as those of a high-quality office building. In structural terms, it consists of a reinforcing concrete table with an underside in the form of a groin arch with a 10-centimeter camber. Laminated wood rafters, supported by oak pin-end columns, form the skeleton and bear the trapezoidal

sheet metal elements of the roof and facade. There is a second layer consisting of Alucobond panels, screwed on as in plane construction.

They have the precise look of a car body. The dark-blue solar facades, frameless and transparent, cover an area of 54 (and 180) square meters and have been incorporated into the building as structural glazing.